The papacy returns to Rome and a great Renaissance pope is born

Pope St. Pius V was born on this day in 1504, before becoming a pivotal figure of the Renaissance and Christian Civilization, and later the first pope-saint in 500 years

1377 A.D.

Today in Papal History marks the official end of the Avignon Papacy – a 70-year exile in the 14th Century where the Successors of Peter holed up in the French enclave and was more or less beholden to the French crown during that time – as Pope Gregory XI returned to Rome.

The pontiff retaking his rightful place in the Eternal City was thanks in no small part to a rather rousing letter written to him by the great St. Catherine of Siena, excerpted below:

Up, to give your life for Christ! Isn't our body the only thing we have?[9] Why not give your life a thousand times, if necessary, for God's honor and the salvation of his creatures? That is what he did, and you, his vicar, ought to be carrying on his work. It is to be expected that as long as you are his vicar you will follow your Lord's ways and example.

So come, come! Delay no longer, so you may soon set up camp against the unbelievers, and so you will not be frustrated in the endeavor by these rotten members who are rebelling against you!

1504 A.D.

Antonio Ghisleri was born in the Lombardy region of Italy 519 years ago today, the son of poor but noble family. His early years were spent as a shepherd - an interesting nod to the future, no less – but at 14 he caught the eye of the Dominican Order, specifically two priests who caught on quickly to his intelligence and simple virtue.

Antonio joined the Dominicans as a novice, taking the name Michele – for St. Michael the Archangel – and was ordained a priest a decade later, in 1528. During his 16 years as a professor in Pavia, in northern Italy, Michele was a professor of philosophy and theology, as well as the master of novices – effectively the guy in charge of forming the youngest Dominicans.

On this last point, he was many times elected to be in charge of various priories – little monasteries, or houses where groups of the novices lived in community. This was a time when morals typical to the clergy and those aspiring to the clergy were at a strikingly low bar – not unlike our current time – and so Michele made it his goal in his formation of young men to insist on discipline and growth in the monastic virtues of humility, silence, and obedience.

More than anything, Michele’s effectiveness as a teacher undoubtedly came from his being a witness first. He was constantly fasting and doing penance, would spend long hours in adoration in front of the Blessed Sacrament, and as the Catholic Encyclopedia recounts, he “traveled on foot without a cloak in deep silence, or only speaking to his companions of the things of God.”

Of course, the zeal and demand for greatness from a man like Fr. Michele rubbed many the wrong way, but he didn’t particularly care. Besides, the Church had other plans for him – when once again his intelligence and virtue preceded him.

The man who would eventually come immediately before Fr. Michele in the Chair of Peter – Paul IV, then known as Cardinal Caraffa – did appreciate the zeal of the holy Dominican, and enlisted his help in numerous roles battling heresy throughout the Christian world, which culminated with him getting a nice red hat and being named Inquisitor General in 1557.

This gave now-Cardinal Ghisleri the license he needed to fight the scourge of spreading Protestantism, and reform the Church of her bloatedness, laxity, and clerical abuses – which he had fought so diligently against since his early days as a priest – this time on a much wider scale.

We’ll cite a brief example, just to show the Cardinal’s fortitude – at the time (as was the case many times throughout papal history), nepotism was particularly rampant. Pius IV, the man who Cardinal Ghisleri would follow as pope in 1566, wanted to make his 13-year-old nephew a cardinal – presumably to win the title of Funnest Uncle – but the stalwart cardinal put up what the Catholic Encyclopedia called “insurmountable opposition” and was able to convince the pope otherwise, in keeping with his “no red hats for teenagers” rule.

Or so we’ve heard.

Upon Pius IV’s death, in early December 1565, the papal conclave was convened and – despite his express wishes against being elected, and thanks to the great support of St. Charles Borromeo, a fellow cardinal – Pope Pius V was chosen as the next successor of St. Peter.

Borromeo, who was also one of the key players at the recently-concluded Council of Trent, supported Pius due to having “a high esteem for him on account of his singular holiness and zeal”, and assured his brother cardinals that the Church would be better with him as pope.

Pope Pius V was officially installed on his 62nd birthday – January 17, 1566. His simple and penitent way of life didn’t change a bit, even after he donned the white cassock – contemporary accounts note that he would wear a hair shirt under his clothes, would frequently be seen traveling barefoot, and despite an insane schedule, would still spend hours in front of the Blessed Sacrament.

Speaking into his regular mode of operations as pope, the Catholic Encyclopedia notes that Pius V,

In his charity visited the hospitals, and sat by the bedside of the sick, consoling them and preparing them to die. He washed the feet of the poor, and embraced the lepers. It is related that an English nobleman was converted on seeing him kiss the feet of a beggar covered with ulcers. He was very austere and banished luxury from his court, raised the standard of morality, laboured with his intimate friend, St. Charles Borromeo, to reform the clergy, obliged his bishops to reside in their dioceses, and the cardinals to lead lives of simplicity and piety.

Pius also forbade bull fights from St. Peter’s Square (because apparently that was a thing back then), enforced fully the decrees of the Council of Trent, supported missions in the New World, and joined the likes of predecessors St. Gregory VII and Pope Boniface VIII as upholders of the supremacy of the papacy over civil powers.

On the sainthood front, likely with childlike giddiness, Pius V declared St. Thomas Aquinas a Doctor of the Church in 1567. To commemorate the occasion, Pius also commissioned the first edition of Aquinas’ works to be produced at the Dominican Headquarters in Rome – known to us now as the Angelicum, or the Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas.

On the liturgy front, Pius V followed the direction of the Council of Trent and standardized the celebration of Holy Mass with the 1570 edition of the Roman Missal (for those unfamiliar, that’s the book clergy use to, essentially, know what words to say and what motions to do during Mass).

The new Missal was implemented throughout the Western Church, except in places where a liturgy was being used that originated from before 1370 AD.

No word on whether the Society of St. Pius I called Pius V a heretic or not.

Paired with the Missal was also a catechism in 1566 and a revised breviary, the manual of prayers prayed daily by all clergy, in 1568. These were in use virtually unchanged for nearly 4 centuries, until Pope St. Paul VI’s revision in the late 1960s – though it’s fair to note that the seed of those reforms stems all the way back to the 1700s and Pope Benedict XIV. But that’s a story for another day.

All of the Tridentine reforms, as they came to be called – those stemming from the Council of Trent – were in service to the surging spread of Protestantism. But Pope Pius V’s crowning achievement was a victory over the Ottoman Turks that has resounded through the centuries, and gone down in history as one of the greatest naval battles – arguably the greatest – of all time.

The day was October 7, 1571 – a little more than 450 years ago – and the battle ... was Lepanto.

Six years prior, just before Pius was elected to steer the barque of Peter, the armies of Suleiman the Magnificent sent his fleet of 40,000 troops to siege the stubborn island of Malta – he had progressively been conquering more and more formerly Christian lands, but the tiny Catholic island nation was the perpetual bee in his bonnet.

“Against all odds,” as Fr. George Rutler recounts in a 2016 essay, “only 10,000 Turks survived to limp slowly back to Constantinople.”

The Ottoman sultan was, naturally, none too pleased – to put it lightly – and spent the next half-decade amassing an army of 300,000 fighters, then massacring all who got in their way as they marched toward Vienna – with Rome being their ultimate goal.

Following the brutal killing of 20,000 civilians in Cyprus’ capital, and the shipping off of 2,000 children as sex slaves to Constantinople (no exaggeration), a frail old man in white would ask stronger and much younger men than he, ones who in normal times were often at each others’ throats, to put aside their differences for the good of the Church – for the good of humanity.

The fruit of Pius V’s effort was known as the Holy League – announced officially at Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome, and comprised of forces from the Papal States, Spain, Genoa, Naples, Sardinia, Venice, and the Knights Templar. England, run by the brutal Protestant tyrant Elizabeth I, and France, already sold out to the Turks, were naturally of no help.

Pius implored the universal Church to aid in the effort – financially by tithing 1/10 of all revenues from monasteries throughout Europe, and spiritually by ordering all churches in Rome to be open for prayer day and night. He, in essence, built up two armies – one to wage physical war, and the other to wage a spiritual one, specifically through the recitation of the Rosary and asking the intercession of Mary, the Mother of God.

For the battle itself, Pius chose Don Juan of Austria to lead the charge – bastard son of the late Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, and half-brother of the Spanish king Philip II. As Fr. Rutler writes, “He was everything the aged and arthritic pope, reared as an impoverished shepherd boy, was not and almost nothing of what the pope was save for his love of Our Lady: a beguilingly handsome flirt and elegant dancer and acrobatic swordsman, who kept a lion cub in his bedroom along with a pet marmoset.

Don Juan was joined by none other than Miguel Cervantes, who after the battle would go on to write the classic story Don Quixote. Both of them were all of 24 years old – as Fr. Rutler rather sardonically notes, “roughly the same age as some modern youth on our college campuses who demand “safe spaces” to shelter them from lecturers whose contradictions of their views make them cry.”

Oh how the world has changed in 4 and a half centuries.

But I digress.

For a full and beautiful recounting of the epic battle, read GK Chesterton’s poem Lepanto, or the full essay from Fr. Rutler here. In short, and against all odds, the world swung as if on a pendulum that day.

Both sides set sail out onto the Gulf of Patras – on the Ionian Sea off the western coast of Greece – and all of the momentum was in favor of the Islamic raiders and against the Christian West. To the strictly worldly minded, it seemed that all of Europe could be under Muslim rule before long, and the Eternal City herself may soon fall.

But it was not to be.

An outnumbered Christian fleet – sallying forth into what surely seemed to be certain death, perhaps to be considered a martyrdom when all was said and done – was suddenly aided by an inexplicable 180-degree wind shift, which Pius V attributed later to the “breath” of Our Lady, if you will. As a result, the Holy League had the upper hand and overtook the Turks in a 5-hour battle that saw all of their ships sunk, nearly 30,000 Turkish casualties, and the freeing of 15,000 Christian slaves.

History tells us that Pius V at the moment of victory – far off in Rome – was in an entirely ho-hum and unrelated meeting, seemingly a world away, when he was graced with a vision of the Holy League prevailing. Although the precise details were never put on paper, Fr. Rutler tells the tale beautifully:

“Pius V saw the scene miraculously while in the church of Santa Sabina discussing administrative accounts with his advisor Bartolo Busotti, and announced the victory to him, nineteen days before a messenger of the Doge of Venice Mocenigo reached Rome with news—no longer new—of the great victory. “Let us set aside business and fall on our knees in thanksgiving to God, for he has given our fleet a great victory.” Five years later the astronomer and geographer Luigi Lilio died. He was a principle architect of the Gregorian calendar implemented in 1582. Trained minds like his, acting upon the testimony of witnesses, calculated by the meridians of Rome and the Curzola isles that the pope had received his revelation precisely as Don Juan leaped from his quarter deck to repulse the Turks boarding his vessel and when the Ottoman galley “Sultana” was attacked side and stern by Marco Antonio Colonna and the Marquis of Santa Cruz.”

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of the Battle of Lepanto. Fr. Rutler goes on:

Had the Christian fleets sunk off western Greece on October 7 in 1571, we would not be here now, these words would not be written in English, and there would be no universities, human rights, holy matrimony, advanced science, enfranchised women, fair justice, and morality as it was carved on the tablets of Moses and enfleshed in Christ.”

Pius V declared October 7, from that day forward, the Feast of Our Lady of Victory, attributing to Mary’s intercession the great victory on the water that day. Victory, indeed.

The humble pontiff had grander plans to further diminish the power of Islam, but he was called to his reward before he could do so. Pius V died on May 1, 1572, after suffering from a painful illness over some months prior.

He was beatified by Pope Clement X in 1672, was canonized by Clement XI in 1712, and is entombed at the Basilica of St. Mary Major in Rome.

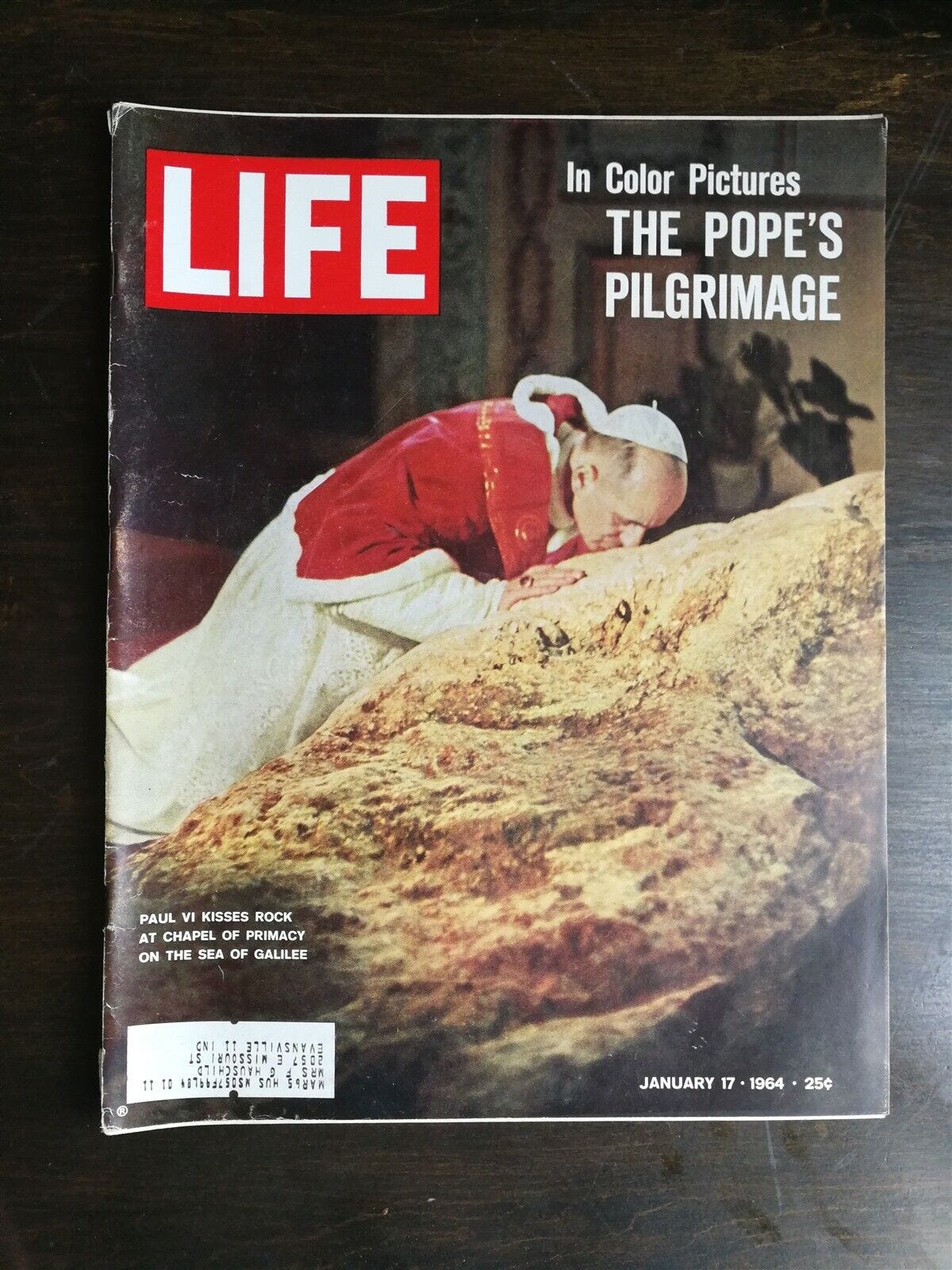

1964 A.D.

One last note for today – 59 years ago, Pope St. Paul VI appeared on the cover of LIFE magazine to mark his historic visit to the Holy Land, becoming the first pope literally since St. Peter himself to set foot in Jerusalem, and also the first pope to ever ride on an airplane.

Fans of Today in Papal History may also be interested in my series of posts on the history of the Second Vatican Council. Join the conversation! https://nickcoccoma.substack.com/p/vatican-ii-part-one