The death of a pope who survived the Black Plague

Also: A pope who was first an antipope, and Ike meets Good Pope John

963 A.D.

Today in Papal History marks the date that a future pope – Leo VIII – started his anti-papacy.

Yes, you read that right.

Leo VIII is indeed the 131st pope of the Roman Catholic Church, but his is an interesting case: before becoming the rightful pontiff, Leo was first an illegitimate one – a pretender to the papal throne.

As the story goes, many in those days sought to get Pope John XII out of office – the man…or should we say boy…who as its youngest claimant in history was basically gifted the papacy by dear old dad, the patrician of Rome at the time, when he was a mere 18(ish) years old.

To paraphrase Dr. Watson, John’s depravity knew no bounds, and as a result Emperor Otto I of Germany, who John himself had crowned, soon grew tired of his antics and sought to have him deposed.

Enter Leo VIII, who was serving at the time as protonotary to the Apostolic See – a word-salad way of saying he was the chief clerk of the papal court. Otto convened what was technically an uncanonical (aka illegal) meeting of bishops to depose John XII and install Leo VIII in his stead.

Leo was still just a layman at the time, so despite his “election” happening on December 4, 963 AD, he still needed to be ordained (wait for it): ostiarius, lector, acolyte, subdeacon, deacon, and priest, all in the span of a day.

Leo’s consecration as a bishop happened on this date 1,059 years ago, and this began his short-lived anti-papacy.

To his credit, Leo would become the true pope in under a year, given John XII’s untimely death – possibly at the hands of his lover’s husband, no less – and the short-lived papacy of Benedict V, who the Romans had chosen to follow John.

Historical consensus has Leo VIII ascending to the papacy legitimately on June 23, 964, where he reigned for just under a year.

1352 A.D.

Also on this day in papal history, Pope Clement VI died after a 10 year stint as the Roman pontiff.

Clement VI was a Frenchman born into one of the wealthiest families of France’s minor nobility, and became a career churchman beginning at age 10, when he entered a Benedictine monastery in what is now south-central France.

After meeting – and apparently impressing – Pope John XXII while teaching in Paris, he was made Bishop of Arras in 1328, then Archbishop of Sens the following year, and finally Archbishop of Rouen in 1330. He was then given a nice red hat by the man who turned out to be his predecessor, Benedict XII, in 1338, and was assigned the church of Santi Nereo e Achilleo.

Clement VI was one of the “Avignon Popes” – the seven men who reigned over the Catholic Church from Avignon, France instead of from Rome – and in fact was the one who not only commissioned the construction of the current Palais des Papes (“Palace of the Popes”) there, but who actually bought Avignon itself from Queen Joanna of Naples. Safe to say that he wanted to ensure that the papacy never left.

Clement was also well-known for lavishly spending on the finer things. The Catholic Encyclopedia notes:

Clement was munificent to profusion, a patron of arts and letters, a lover of good cheer, well-appointed banquets and brilliant receptions, to which ladies were freely admitted. The heavy expenses necessitated by such pomp soon exhausted the funds which the economy of Benedict XII had provided for his successor.

Despite all of this, and his love for appointing relatives to key posts in his curia, Clement VI is most associated with something entirely outside of his control – being the man in charge of Christendom when the Black Death began tearing through Europe in 1347.

The pope somehow managed to avoid being one of the roughly 100 million people who succumbed to the epidemic – one that apparently caused swelling in the armpits and groin, along with producing black splotches on the skin – and used his good health to ensure care for the sick and dying, going as far as consecrating the entire Rhone River as holy ground when cemetery space became scarce.

He also very loudly advocated for the Jewish people when certain factions began to suspect them as the cause of the plague and persecuted them as a result. Clement issued the papal bull “Quamvis Perfidiam” in 1348 noting that:

It cannot be true that the Jews, by such a heinous crime, are the cause or occasion of the plague, because through many parts of the world the same plague, by the hidden judgment of God, has afflicted and afflicts the Jews themselves and many other races who have never lived alongside them.

Further, Clement minced no words in saying that anyone who blamed the Jews for this great affliction had been “seduced by that liar, the Devil.”

On the day of Clement VI’s funeral in 1352, the papal almoner – the pope’s designated man for giving alms to the poor – distributed large sums to the poor who were present at the procession. The historian Gregorovius later described Clement as “a fine gentleman, a prince munificent to profusion, a patron of the arts and learning, but no saint."

1959 A.D.

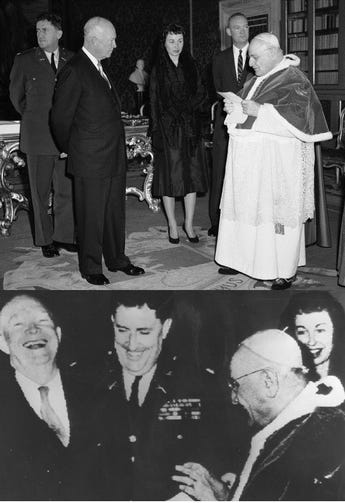

On a more contemporary note, Today in Papal History also marks the occasion of President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s meeting with Pope St. John XXIII.

“Good Pope John” was reportedly always a bit self-conscious of his inability to speak English, but wanted to help his esteemed feel more welcome by saying a few words in the latter’s native tongue. It didn’t quite go as planned, but president and pope were easily able to have a good laugh at the attempt.

From a story in American Magazine in 2015:

Pope John began his address of greeting to the president of the United States. After a time, the reporters who were present looked up from their notes, puzzled. What they saw was an amazing sight: both pope and president had their heads thrown back in raucous laughter. It seemed that the pontiff, in speaking his few words of greeting for his prestigious visitor, had stumbled in that part of his address which he had studied and rehearsed for so long. Pope John burst out in comfortable Italian: “Era di Belli!” which in English came to: “That was a beauty!” or “That was a beaut!”

President Eisenhower, listening attentively, caught the drift of the pope’s Italian, threw his head back and laughed heartily, appreciating the Italian version of American slang. Pope John, seeing Ike’s reaction, did the same. So the entire company in the papal apartments erupted in happy laughter, a rarity for those solemn Vatican halls. But it was welcome nevertheless, and the cameras clicked to record this historic moment. A photograph immediately went all over the world of pope and president engaging in a moment of levity. No doubt those entrusted with papal and presidential protocol were left less than amused at what had happened.