An election controversy and an imprisoned pope

Two pontiffs of the Middle Ages facing a bit of drama – one the target of a nearly-stolen election, and the other a fixture in Dante's Inferno who got a dose of his own medicine.

1159 A.D.

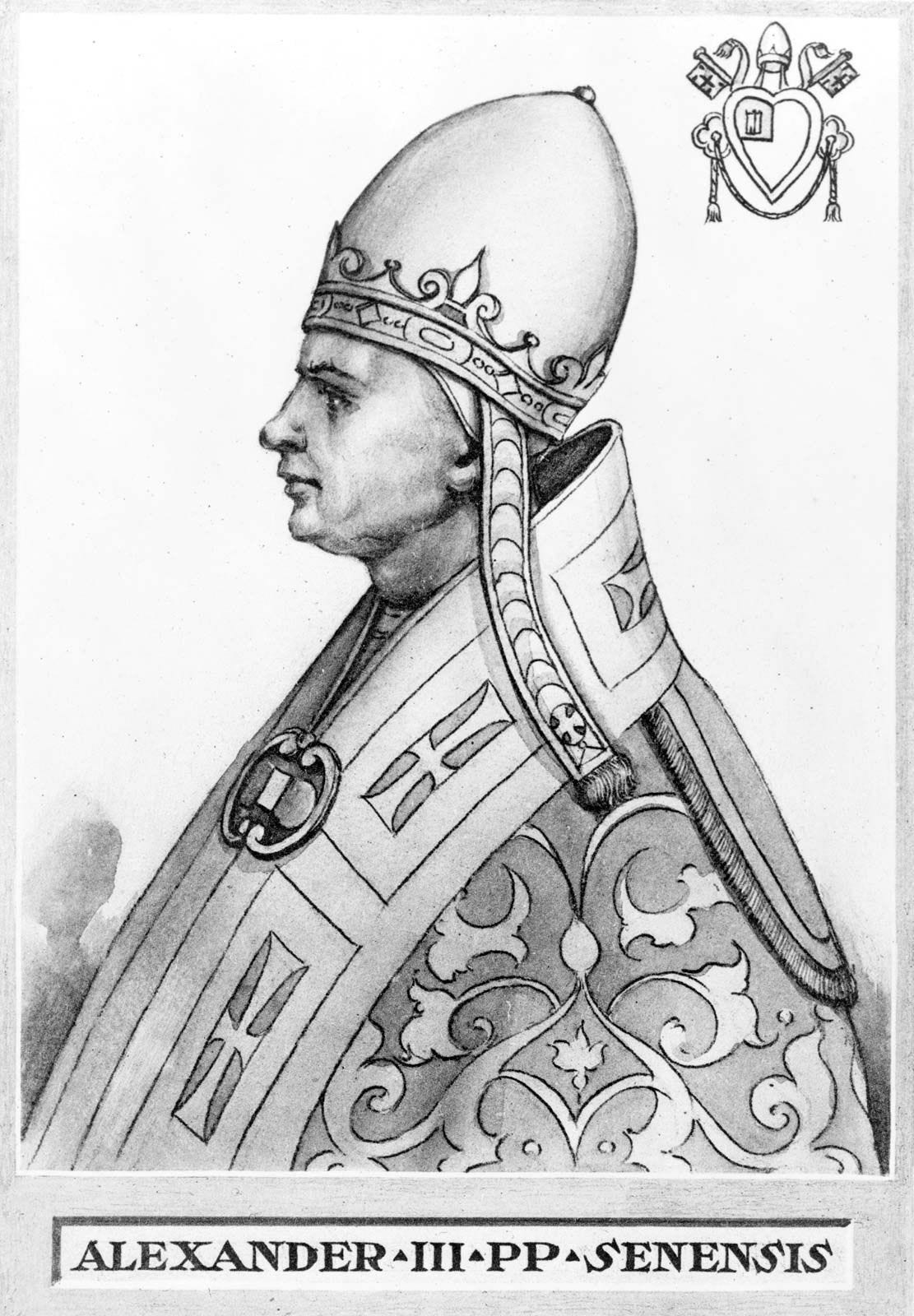

Today in Papal History, Pope Alexander III was chosen as the 170th Bishop of Rome, beginning a reign that stands today as the seventh-longest papal tenure in the history of the Catholic Church.

But Alexander’s beginning, 863 years ago today, was anything but smooth sailing.

Prior to his election, Alexander – born Rolando Bandinelli in the year 1100 to a prominent family in Siena – had served as a cardinal in the court of Pope (Blessed) Eugene III beginning in 1150 and then as chancellor for Eugene, Anastasius IV (1154) and finally Pope Adrian IV, his immediate predecessor.

He was regularly sent on diplomatic missions to negotiate between the papacy and secular rulers, and two years prior to Alexander’s election he found himself across from the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick Barbarossa, at the Diet of Besançon in 1157.

Barbarossa – who was holding the meeting to hear papal pleas about releasing Eskil, the Archbishop of Scandinavia who had been imprisoned for opposing him – had been at odds with Adrian for some time on these and other issues (to keep a long story short), and so tensions were already a bit high when the future Alexander III and another papal delegate arrived on the scene.

To the papal legates’ credit, they were described by Barbarossa’s court historian as:

“distinguished for their wealth, their maturity of view, and their influence, and surpassing in authority almost all others in the Roman church.”

But a faulty translation in the reading of Adrian IV’s letter to Barbarossa managed to offend the emperor beyond repair (calling the emperor a vassal of the pope will do that…).

A couple of attempts were made to clarify the translation, and it likely wasn’t Alexander’s fault either way, but the damage was done. And so, by the time of Adrian IV’s death in 1159, the cardinals were firmly divided into two camps: the imperialists (fans of the emperor) and those, as the Catholic Encyclopedia notes, “sought to escape the German yoke (i.e. Barbarossa) by alliance with the Normans of Naples.”

Despite Barbarossa’s work to drum up more support for a papal patsy, Cardinal Rolando received all but three votes out of the 22 cardinals present on September 7, and took the name Alexander III.

The emperor, however, wasn’t about to give up. The three cardinals who voted against Alexander chose Octavian from among themselves to serve as a rival pope, who styled himself Victor IV.

Both parties were forced to flee after a mob broke up the conclave soon afterward, but each man was consecrated pope in his respective hiding spot – Alexander in Ninfa and Victor at Farfa.

Barbarossa tried and failed to hide his allegiance when he called a meeting at Pavia to settle the matter, referring to the antipope as “Victor IV” and as the legitimately elected successor of Peter as “Cardinal Rolando”, and Alexander III refused to attend as a result.

What ensued was 18 years of a formal schism in the Catholic Church, with Alexander and Barbarossa mutually excommunicating one another and the pope being forced to live anywhere but Rome for the majority of his papacy.

Alexander III was opposed by four antipopes in all by the time of the battle of Legnano in 1176, in which Barbarossa’s forces were soundly whipped by both man and disease, resulting in the emperor admitting defeat and making peace with the man he had so fiercely opposed for two decades.

Now, Alexander wasn’t one to rub a man’s nose in it, so he saw to it that schismatic bishops and cardinals were pardoned and that even the current antipope, Callixtus III, was given a prominent role in Benevento in which to live out his days.

For his part, Alexander also notably presided over the Third Lateran Council in 1179, which produced, among other things, the still-practiced rule that two-thirds of the cardinals must vote for a single candidate in a conclave in order to choose a new pope.

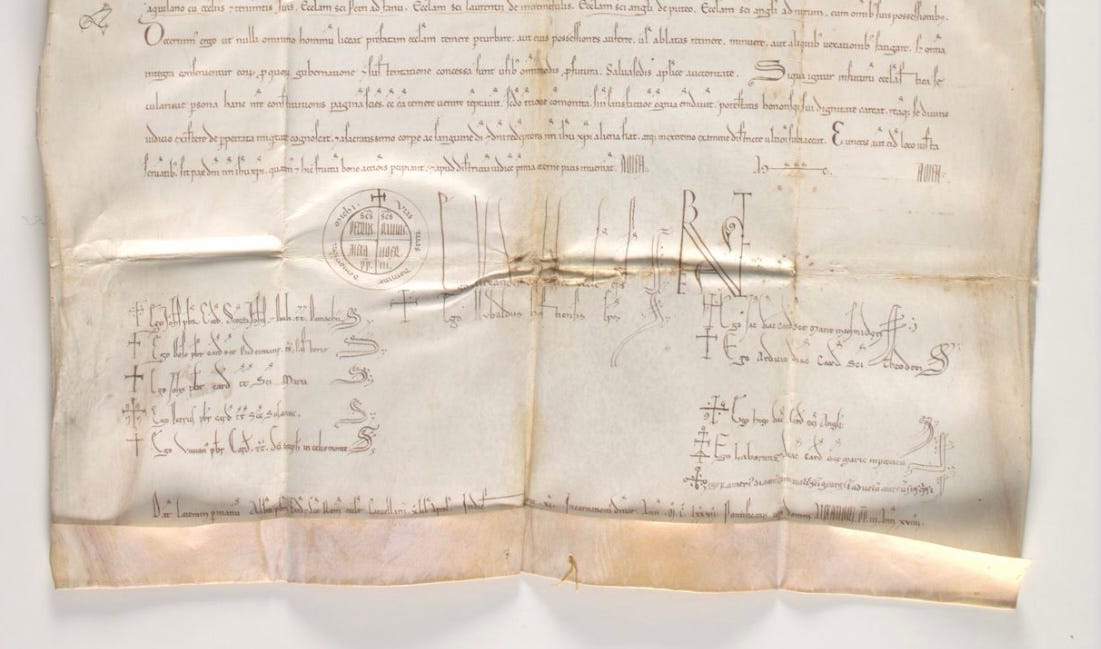

And believe it or not, there still exists a document with the signature of Pope Alexander III and three other future popes – a “Great Bull” currently in the possession Fr. Richard Kunst of the Diocese of Duluth (Minn.) and papalartifacts.com.

1303 A.D.

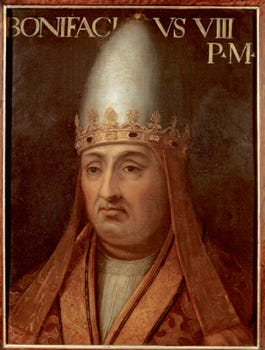

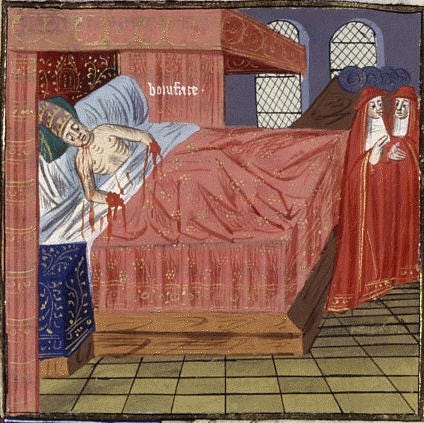

Nearly nine years had passed since Pope Boniface VIII’s elevation to the papacy by the time September 7, 1303 rolled around, and his time on earth was running out.

Boniface, who was born into the generational powerhouse Caetani family around 1230 AD, is one of the more recognizable figures of the medieval papacy, having succeeded St. Celestine V, the last man to abdicate the Chair of Peter before Pope Benedict XVI did it in 2013, possibly after pressuring the old hermit to resign in order to take his place.

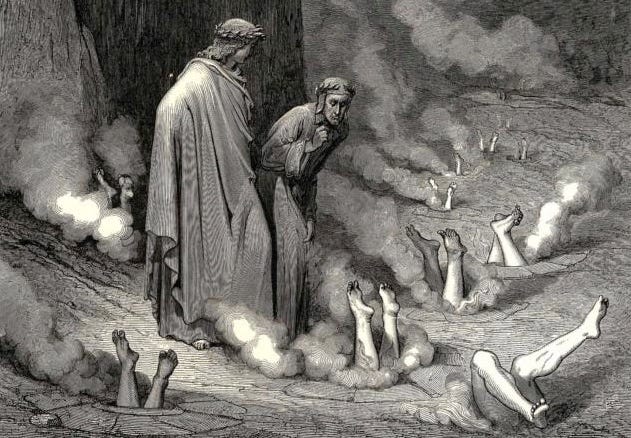

He’s also notoriously found in Dante’s Divine Comedy, residing in the Eighth Circle of Hell, having damned him for the sin of simony (or maybe just because Dante hated him…)

And specific to our topic today, Boniface VIII made stronger claims to the temporal authority of the papacy than nearly any other before or since, claiming absolute authority over emperors and kings. This ended up getting him in a fair bit of hot water with King Philip IV of France, in particular.

The two traded diplomatic barbs over the course of the first few years of the 1300s, culminating in an excommunication of Philip IV by Boniface and the placement of a special papal legate to the King in the event that Philip decided to repent.

Spoiler: He didn’t.

Boniface then decided to escalate things again, doling out more excommunications and strongly-worded letters. And because that always works so well, Boniface received in response a visit from an army led by Philip IV’s chief minister, Guillaume de Nogaret, who seized the pontiff and likely beat the 73-year-old man nearly to death.

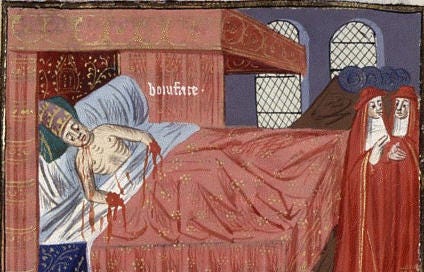

Boniface VIII was held for three days beginning September 7, 1303 before being released, but he would never recover. Giovanni Villani, a contemporary historian from Florence, wrote about Boniface’s imprisonment and final days:

And when…his enemies came to him, they mocked at him with vile words and arrested him and his household which had remained with him. Among others, William of Nogaret, who had conducted the negotiations for the king of France, scorned him and threatened him, saying that he would take him bound to Lyons on the Rhone, and there in a general council would cause him to be deposed and condemned.... no man dared to touch [Boniface], nor were they pleased to lay hands on him, but they left him robed under light arrest and were minded to rob the treasure of the Pope and the Church. In this pain, shame and torment, the great Pope Boniface abode prisoner among his enemies for three days.... the People of Anagni beholding their error and issuing from their blind ingratitude, suddenly rose in arms... and drove out Sciarra della Colonna and his followers, with loss to them of prisoners and slain, and freed the Pope and his household. Pope Boniface... departed immediately from Anagni with his court and came to Rome and St. Peter's to hold a council... but... the grief which had hardened in the heart of Pope Boniface, by reason of the injury which he had received, produced in him, once he had come to Rome, a strange malady so that he gnawed at himself as if he were mad, and in this state he passed from this life on the twelfth day of October in the year of Christ 1303, and in the Church of St. Peter near the entrance of the doors, in a rich chapel which was built in his lifetime, he was honorably buried.

1978 A.D.

To close out this edition of Today in Papal History, here’s an excerpt from an address given 44 years ago today by Blessed Pope John Paul I, who was just beatified over the weekend. Click here to get the full story of his life and legacy.

In an address to Roman Clergy on September 7, 1978, John Paul said this in closing:

It is not easy, I know, to love one's job and stick to it when things are not going right, when one has the impression that one is not understood or encouraged, when inevitable comparisons with the job given to others would drive us to become sad and discouraged. But are we not working for the Lord? Ascetical theology teaches: do not look at whom you obey, but for Whom you obey. Reflection helps too. I have been a bishop for twenty years. On several occasions I suffered because I was unable to reward someone who really deserved it; but either the prize position was lacking or I did not know how to replace the person, or adverse circumstances occurred. Then, too, St Francis of Sales wrote: "There is no vocation that does not have its troubles, its vexations, its disgust. Apart from those who are fully resigned to God's will. each of us would like to change his own condition with that of others. Those who are bishops wish they were not; those who are married wish they were not, and those who are not married wish that they were. Where does this general restlessness of spirits come from, if not from a certain allergy that we have towards constraint and from a spirit that is not good, which make us suppose that others are better off than we are?" (St Francis of Sales, Oeuvres, edit. Annecy, t. XII, 348-9).

I have spoken simply and I apologize for it. I can assure you, however, that since I have become your Bishop I love you a great deal. And it is with a heart full of love that I impart to you the Apostolic Blessing.